No Reservations

Docent Notes

Richard Klein

Bill Schott

White Providence and American Indian Circumstance

Notes on

No Reservations: Native American History and Culture in Contemporary Art

No Reservations is a group exhibition of ten contemporary artists whose work focuses in one way or another on the history of Native American people and culture, on view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum from August 23, 2006, to Feb 25, 2007.

Of the exhibiting artists, those who are non-Native seem to be generally more interested in the history of Native Americans because it sheds light on the supposed “American Character.” The Native contingent in the exhibition seems to be more interested in reclaiming Native American culture and traditions. In either case, the central story of the United States and the occupation of North America, the dislocation of Native people, and their genocide, is one that we all know. However, one might argue that this history is not as readily accessible or thought of as much as other histories. By bringing together this collection of work, No Reservations examines the Native American culture through a lens of contemporary art-making.

Lately, there is the expectation in Germany that younger generations have come to terms with the Holocaust and their country’s Nazi history. In general, the younger generation is more able to deal with it. This is evident through the willingness to engage in conversations that would not have taken place during the 1950s and 1960s. This sort of openness has never really occurred regarding the history of the Native Americans and the United States. When you look at the extreme things that were done to the Natives, in particular between the 1840s and the 1890s, you see that similar atrocities were committed, only that these seem to have been forgotten or, even worse, swept under the carpet.

Upon investigation, one quickly learns about an unbelievable string of lies that were told to Native people; of treaties signed and murderous acts committed on behalf of the American Government—it really is a horrible story. This exhibition does not dwell on the past. However, it does acknowledge this history and raises more questions than answers about how we currently view Native American history and culture.

The non-Native artists who are dealing with these issues are looking at this history and are trying to get to some central issue about “American character.” In many ways, it is revealing of human nature in general. It shows the dark side of human nature and what is evil in human beings. By analyzing how this came about, the artists realize how history can inform us, and are making work so that viewers can become aware of it.

Native American culture reminds us that we are all habitants of this land. Regardless of where we came from, we all live here now, and being aware of this tenancy puts us closer in touch with the American landscape. It grounds us. It encourages us to be good citizens and become politically aware of related topics. When you research the American Indian Movement, you realize that what happened was not that long ago in relation to the entirety of human history and recorded time.

Since the subject matter of Native American history and culture is very broad, Richard Klein, the curator, wanted to limit the number of artists (10) so each could show multiple works. This was done deliberately, so that there is a more complete showing of each. Overall, it is an interesting mix because there are many ways to go with this theme. Also, it marks the first time that The Aldrich has shown an artist from Alaska.

MATTHEW BUCKINGHAM

Matthew Buckingham

The Six Grandfathers, Paha Sapa, in the Year 502,002 C.E., 2002

60 x 43 black and white digital c-print, dry-transfer wall text

Installation dimensions variable

Matthew Buckingham is a non-Native American artist, who has moved around frequently. He has lived in New York, London, and other places. He currently lives in Minneapolis.

He has two really amazing projects about Native American history. One of them is entitled The Six Grandfathers, Paha Sapa. It is a large digital photograph of what is now Mount Rushmore, in 1050 BCE. Mount Rushmore is part of the Black Hills. ‘Paha Sapa’ is Lakota, the local Native language, for Black Hills, which were, and still are, sacred lands to the local Natives.

Matthew’s photograph documents what the Black Hills will look like in 500,000 years from now. It shows how the United States monument will get to the point where you cannot recognize the faces of the presidents anymore. The work also includes the history of this region from prehistoric times to today.

In researching the Native American language one finds that the English language has changed the names for many things. For instance, the name Dakota is an American version for Lakota. Both refer to the same thing, except that there is some controversy over what constitutes tribal names, since many names were given by early European American settlers. Currently, there is a movement to go back to the old/ original names.

The accompanying timeline in this work outlines the affront that was given to Native people with regard to the Black Hills and the construction of Mount Rushmore. It dates significant geological occurrences, as well as the corrupt politics of the US government when it was being made. Gutzon Borglum, the creator of Mount Rushmore, had previously worked on Stone Mountain in Georgia. There are only four presidents depicted because he only had the budget to carve four of them.

When thinking about the significance of this work, it is important to think that here is a European-American artist focusing on an iconic American image (Mount Rushmore). He is projecting forward in geologic time, instead of looking back, making the point that nothing lasts forever. The permanence of all things fades. Even the most resilient empires crumble. There is a common misconception about the idea of owning land and drawing boundaries (house fencing, state and national borders). A concept of Native American teaching is that it looks at land ownership in a much different way. Territory and homeland still exist, it is just a much more fluid thing. We only borrow the land we live on while we are alive.

LEWIS deSOTO

Lewis deSoto

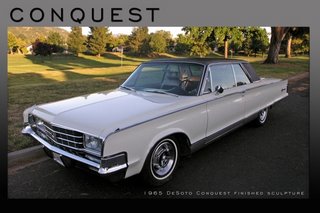

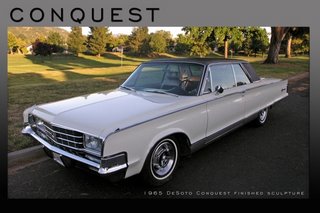

CONQUEST, 2004

Full-size customized motor vehicle

4 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. 6 in. x 18 ft. 6 in.

Lewis deSoto is a Native American artist who grew up in Napa, California. His paternal great-grandfather’s side of the family is linked to both the Cahuilla tribe and to ancestors of Hernando DeSoto, the sixteenth century Spanish conquistador. His great-grandfather was from the same small town in Spain as Hernando DeSoto. With the same last name (though different capitalization), the artist believes they are blood-related, though they still lack official documentation. Regardless, Lewis deSoto’s great-grandfather, after moving to North America, married a member of the Cahuilla tribe. Lewis therefore has relations to both the “conquered” and the “conquerors.”

For this exhibition, deSoto will present two cars in the Museum lobby and Project Space.

In the lobby is an automotive self-portrait that conceptually references the history of Hernando DeSoto, the Spanish conquistador who pillaged southeast and midwest America in search of New World riches during the sixteenth century. From the 1920s to the 1960s, Chrysler owned a marque named after the Spanish conquistador, entitled “DeSoto.” Well, Lewis deSoto grew up in California and became fascinated with car culture. While growing up, and to this day, Lewis was frequently asked if there is a connection between his family and this car company. The DeSoto company went out of business in 1961, and the line of cars was discontinued. Lewis has since found an older Chrysler model and restored and fabricated it to become what he now refers to as a 1965 DeSoto CONQUEST. People who know a bit about cars will ask how there is a 1965 model. To this Lewis replies, “they continued production in Canada for a couple more years.” Of course, in fact, they did not!

Apart from using an older model as the platform, Lewis deSoto also redesigned instruments, wheel covers, roof designs, monikers, upholstery, color schemes and mechanical characteristics to suit the concept of the CONQUEST. In addition, the owners manual and window sticker include the Requiremento, the legal document read to Native peoples before their submission to Spain (poster of this will hang in the exhibition space). Overall, this design is meant to mesh with the idea of synthetic histories of DeSoto’s supposed conquest of the Americas.

LEWIS deSOTO

CAHUILLA, 2006

Full-size customized motor vehicle with ambient soundtrack

6 ft. 6 in. x 7 ft. 11 in. x 18 ft.

Tapestry weaving courtesy Magnolia Editions, Oakland, CA

The second piece by Lewis deSoto is the CAHUILLA pickup truck. It is a 1981 GMC pickup converted into a new model called the CAHUILLA. The vehicle is named after his great-grandmother’s tribe; the Cahuilla tribe has a casino and has made quite a bit of money recently. This truck is looked at by the artist as a symbol of the Cahuilla culture and has incorporated traditional views from their history. It also incorporates the reality that many Indian tribes are involved with recent casino development. When you look down from the balcony of the Project Space upon this piece, you will see a woven tapestry stretched over the bed of the truck. Traditional Cahuilla designs are used along with black diagrammatic drawings that represent a craps table from a casino. A soundtrack of Native chants with ambient noise from slot machines will play on the internal sound system in the truck. In addition, the truck has all sorts of subtle things: from the traditional necklace made by his grandmother hanging from the rear view mirror, akin to a talisman (like a spirit catcher), to seat covers that are custom-woven with a pattern from the complicated lacy border design of the dollar bill. There is a teepee symbol as an automotive logo on the side of the vehicle, as well as a bumper sticker that says “Buy America Back!” This isn’t far from the truth. Aside from casino implications, the Pequots, for example, are literally buying real estate back in eastern CT and providing a great deal of business for major commercial real estate agencies. In many ways, the money from casinos is indeed buying Native American land back. The trick then, for the Native Americans, is in getting the US government to concede and recognize this bought-back land as additional legalized reservation territory. There are many legal incentives for tribes to obtain federal recognition, primarily, the absence of taxation for reservations in the US tax structure.

Lewis’s CAHUILLA project underscores these economic issues and what Native peoples are doing to become financially successful today. He is imagining this truck as being owned by a wealthy casino-working Cahuilla, who lives on the reservation. This exhibition is occurring at a time when immigration is a huge issue for the United States. The comparison of European immigration to North America and the displacement of Native peoples in relation to this contemporary movement of people from Latin America to above the Rio Grande, is most intriguing. The economic displacement that comes from this movement of people, and then the associated politics surrounding financial and territorial ramifications, can become rather cutthroat. However, it is nothing new to civilization. This sort of thing occurs frequently throughout history and all over the world. It is a phenomenon of spatial relations within human existence.

It is well known how American car manufacturers love using Native-American names (e.g. Pontiac, Tacoma, Cherokee; there is a new pick up “Denali” that is named after the tallest mountain in the US, Mount McKinley, Denali is the native name for this location). The car as an object is a symbol of the American landscape. Think about Manifest Destiny and the spread of European civilization in North America. Wagon trails, railroads, and then the automobile. It has led to the subsequent alteration of the environment, with the building of the Interstate highway system, which, probably more than anything else, is responsible for the destruction of so much of natural North America. It has allowed urban sprawl, the kind of suburban development that is endemic in the US because of the car. If you look at the landscape as sacred, the car is the tool that has been the landscape’s undoing more than anything else.

PETER EDLUND

PETER EDLUND

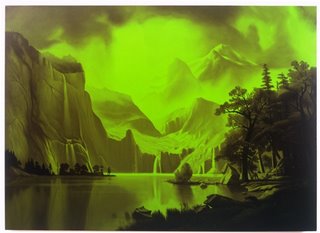

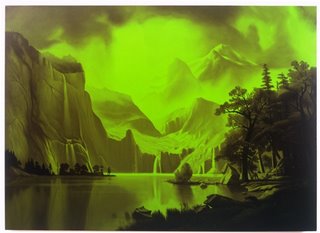

Majestic America: Rape of the Modoc in Yosemite (After Albert Bierstadt), 1999

Oil on Canvas

36 x 50

Collection of John Burger, M.D.

Peter Edlund is a non-Native artist who lives in NYC. His work from the past fifteen years primarily focuses on radical repainting of nineteenth-century American Hudson River School landscape paintings. Artworks from artists such as Albert Bierstadt or James Audubon are mimicked. Yet, all of Peter’s work does not deal with native history. Peter uses the nineteenth century as a lens to talk about the present day. The fact that the nineteenth century was such a formative period for the United States is a corollary. He uses Audubon’s images and Hudson River painters to talk about ecological concerns. He has created work focusing on Native Americans from part of a series called Majestic America. One of these pieces, entitled The Rape of the Moduk at Yosemite Valley, is after Bierstadt. In 1864, the year the original painting was created, the then California authority instigated genocide against the Moduk Indians, who live in the Sierra Mountains. Peter has taken the history of this time and incorporated subtle changes into the landscape painting. The first, which is the most obvious, is that the color is very apocalyptic, menacing and intense. This painting is done to the exact same size as the original and oddly enough it is owned by Sprint and hangs in their corporate headquarters when not on exhibition. Also, subtle changes are visible in the shadows of the painting. When looked at closely, one can see shadowy figures where the Moduk are being raped. Peter has included this change to the painting so as to incorporate the history of 1864. In the painting by Bierstadt, one can see the figures doing something, though it is too hard tell what is going on.

There will be three paintings in total. For this exhibition, he is producing a new version of Frederick Church’s painting of West Rock in New Haven. So it is specifically about CT. Within his work, he studies native language place names. For instance he will look into names like, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Housatonic, Katonah, in order to find the original meaning from the local Native language and will then paint a picture, from his imagination, of the literal translation for the place name. Creating an image from the language is like going backwards with the typical painting process. These paintings will exist in the Project Space with deSoto’s CAHUILLA pick-up truck.

NICHOLAS GALANIN

NICHOLAS GALANIN

Tlingit Raven Vol. 14, 2006

Paper: 1700 pages containing text from Under Mount Saint Elias

6 x 9 x 4

Courtesy of the artist

Nicholas Galanin, a Native American, is the first artist from Alaska to exhibit at The Aldrich Museum. He is from Sitka, Alaska and is part of the Tlingit (pronounced Clink-get) tribe. Of all the Native artists in the show, Galanin summarizes the position that so many Native artists have, with one foot in two different worlds. On one hand, he makes traditional Tlingit artworks, such as wood carvings, totem poles, and other massive wooden objects that are unbelievably accomplished works that are dedicated to his people. At the same time, he also produces contemporary artworks to engage the outside world. His Web site reflects this in how it is divided into two halves (Traditional and Contemporary).

For this exhibition, three works by Nicholas—one video, and two small sculptures—will be shown. One sculpture, entitled Tlingit Raven Volume 14, is taken from a traditional carving of a raven from within Tlingit culture. The contemporary twist is that it is made from pages within a book—approximately 1700 hundred pages from the book Mount Saint Elias, published in 1972 by anthropologist Frederica de Laguna. Laguna was a contemporary of Margaret Mead, and made the definitive study of the Tlingit culture by an anthropologist. All of Galanin’s work is based in this idea that Native people are defined by, or know their history through Western anthropology. So much was destroyed culturally, yet anthropologists are the ones who piece it back together. It is important to note that they are not Native but European. Therefore, Galanin is creating a traditional Tlingit image made out of writings in which a Western anthropologist describes his culture. It is about how a culture gets recreated, or how the culture looks at itself.

JEFFREY GIBSON

JEFFREY GIBSON

Mythmaker, 2006

Wood, urethane foam, oil paint, glass beads, pigmented silicone

114 x 54 x 54

Jeffrey Gibson is a Native American artist. His mother’s side of the family is part of the Choctaw (pronounced chalk-ta) tribe from Mississippi. His father is an engineer and he grew up traveling around the world, living in Germany and other places. He has been exposed to a great deal of international influence, but spends a lot of time in Mississippi on his reservation. He is an example of an artist in the exhibition who incorporates Native/cultural influences in ways that are most unexpected. In the exhibition, he is the Native artist whose work is most devoid of politics. He is really interested in the idea of looking at Native art prior to colonization, and how it was engaged in nature in a very celebratory way.

JEFFREY GIBSON

Residual Urge, 2006

Urethane foam, wood, pigmented silicone

148 x 115 x 27

Silicone courtesy of General Electric Company, Fairfield, CT

He will have both a large sculpture and some paintings on exhibit. His sculpture will be hanging on the outside front of the Museum by the bay window. A foam-filled form covered by millions of silicone rubber beads. It will be heavily textured and mostly black, but with a few flashes of color (red and blue). This way of working is in many ways a continuation of Iroquois pieces called “Beaded Whimsies.” In the nineteenth century, the Iroquois were very poor and to make money made beaded objects for tourist sale. They would make things using traditional beaded techniques, like picture frames, lampshades, and bags. The beading got so intense that some of these objects would become functionally unusable due to the amount of adornment. So here we have a Native beading tradition that was subverted by commerce and turned into a bizarre art form that was very popular for a thirty-year period.

Fully aware of this history, Jeff is now making the largest beaded whimsy ever made. Instead of glass beads he beads with silicon rubber. The complicated beaded surface that covers this foam object turns it into a rather odd and anomalous thing that will hang from the top of the Museum. It can be considered a subversion of the colonial architecture of the Museum, as this piece will also hang in the historic district of Ridgefield. In fact, almost all the houses on downtown Main Street are based in a European architectural style that was predetermined by early accepted colonial aesthetics. So this odd object on the face of the Museum is potentially turning the tables around on this European American aesthetic, by exposing this great growth of Native American financially-necessary adornment. One could critically acclaim this work with heavier politics of building upon the Iroquois tourist trade, but the artist thinks of it much more as a celebratory thing.

RIGO 23

RIGO 23

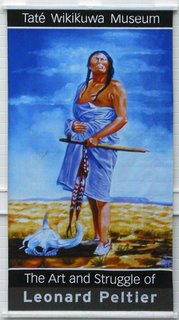

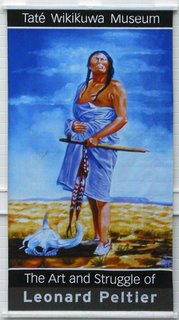

Taté Wikikuwa Museum, 1999-2006

Mixed media installation

Dimensions variable

Leonard Peltier paintings on loan from L.P.D.C.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

The sign out by the street that says, “The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum” has a convenient blank space right under the Aldrich text on the glass. When you come to The Aldrich Museum during the months of No Reservations (starting on August 23), you will be surprised to see that the sign will also feature text that reads Taté Wikikuwa Museum. When you come up the walkway to the Museum, you will also see Taté Wikikuwa Museum on the front of the building, and on the rear of the Museum, in raised letters it will say Taté Wikikuwa Museum. Taté Wikikuwa is the name of Native American activist Leonard Peltier in his Lakota language, meaning “wind chases sun.”

The Aldrich will host this homeless museum that travels around the world and is dedicated to Leonard Peltier, who has been in prison for thirty years. This is a work by an artist named Rigo 23. Yes that is his name, and every couple of years, he changes the number at the end of his name (e.g. Rigo 42, Rigo 99 etc.). Rigo is from the Madeira Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, owned by and just off the coast of Portugal. Curiously, it was a way station for Columbus before he traveled to the New World. Columbus even briefly lived there. Rigo 23 lives in the San Francisco Bay area today and is a social activist. His first work was a mural painting in the spirit of Mexican Muralists. In San Francisco, he was part of the street art phenomenon. However, Rigo’s work was more mural-oriented, with the idea of doing things for communities and giving back to society through art that carries a social purpose. From living in CA, and befriending some Native people, he became aware of Leonard Peltier. Since he is very socially aware and connected, he readily began working with the Native American community.

Leonard Peltier is an American Indian activist who was imprisoned in 1977 for the alleged shooting of an FBI agent on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota. His story is actually the subject of a movie that Robert Redford bankrolled and starred in, made through Sundance Film Festival, entitled Incident at Oglala. It is not a dramatization, but rather more documentary in format, about Leonard Peltier. Rigo has taken it upon himself to work with the Leonard Peltier Defense Fund to try and get him released from prison. Two Native people who were also charged with shooting the agent were released and were never put in prison. Peltier, on the other hand, was charged with aiding and abetting, and, supposedly because he is so vocal, and because of his personality, he was made a scapegoat. In 1999, Bill Clinton was about to release Peltier, but the FBI found out about it, and since they are vehemently against Peltier, they stopped this. In 2008 he is coming up for parole again. He was sentenced to two consecutive 25-year terms, plus a 7-year term for a related crime. At this parole meeting there is the possibility that the board may choose to have him serve his terms concurrently instead of consecutively, so that he could be released in 2008.

Rigo 23 has taken this Taté Wikikuwa Museum around the world (San Francisco, Brazil, Spain, England, etc) to increase consciousness of Peltier, in the hope that the people who see the exhibition will write to the parole board to urge his release. Apparently, parole boards really pay attention to letters. From Amnesty International, to Mother Teresa, to Desmond Tutu, the list of people who support him is rather extensive. Outside the United States he is looked upon as a major political prisoner of the US.

So, in the Balcony Gallery, Rigo 23 will display the museum—a recreation of Peltier’s prison cell. On the back stairwell, dates will go down each step for every year Peltier has spent in prison. In addition, there will be a selection of the paintings Peltier paints in prison. We are actually borrowing these from his legal Defense Fund. The windows will have bars on them so as to recreate the environment of being contained in prison. Information about Peltier and how to contact the parole board will also be made available.

Before I said that the non-Native artists are primarily dealing with history, well this is living history, and this is also with regard to something that happened not too far in the past (from the 1970s). Too many Americans have forgotten about the American Indian Movement (AIM) and how important it was and still is. One thing about Rigo 23’s involvement with Peltier’s Defense Fund, is that he is greatly increasing consciousness of a period of American history that was vital for Native Americans. Nowadays, when you mention Peltier’s name, most people have no clue who he is. So this work acts to remedy that and hopefully aid in his release.

DUANE SLICK

DUANE SLICK

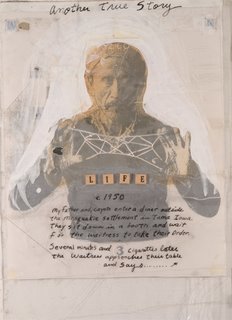

Looking for Orozco (detail), 1993

Mixed media artist’s book on Mylar

15 double-sided pages excerpted from the 17 page book.

Each 22 x 15 1/4

Courtesy of the artist and Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA

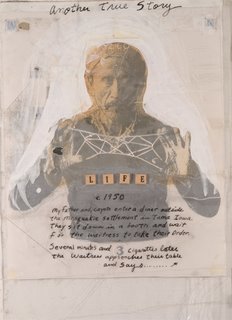

Duane Slick is a Native American artist who is most connected with the Sauk and Fox tribe in Iowa. These people were displaced from the Ohio River Valley. He has recently been spending time out there because his father is very ill. When not in Iowa, he is a professor of painting at RISD.

Duane does two very different bodies of work. One informs the other. The first is a series of artist books, which he has shown in various formats. We will be showing the majority of the pages from an artist book that is a narrative that weaves the influence of Mexican mural painters, from when he was a young man, to his desire to make art that has a social purpose. It includes many experiences that the artist has had with his family, through his relatives, and personally, that pertain to Native American culture.

DUANE SLICK

Looking for Orozco (detail), 1993

Mixed media artist’s book on Mylar

15 double-sided pages excerpted from the 17 page book.

Each 22 x 15 1/4

Courtesy of the artist and Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA

Each page will be hung off the wall perpendicularly and the pages are two-sided. Walk down the wall and look at both sides to read the narrative. The book deals with all sorts of interesting things, including how the artist rejected Jackson Pollock as an influence. A theme that runs through most of the Native work in the exhibition, is being influenced by modernism and working within the modernist tradition, but at the same time wanting to reject it, and wanting to go back a step somehow.

Also on view will be one large painting by Mr. Slick. Duane’s paintings combine Native American mythology and contemporary imagery with a somewhat tragic melancholy feeling. For example, the painting we will show combines an image of an eagle with a wheelchair. We tend to think of the eagle as an all-powerful symbol of Native American and United States cultures. What does it mean when an artist combines it with a wheelchair? It talks about this traditional symbol as being crippled somehow. Also, these images are painted in a very ghostly manner. They could be described as ‘white on white’ paintings and it seems as though he deals with images from a spiritual realm, or images that are not visually apprehended as much as apprehended through one’s mind’s eye, or as a spiritual revelation.

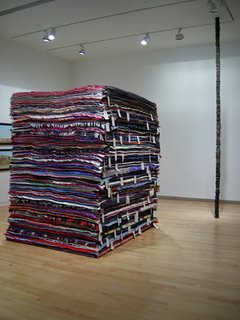

Marie Watt

Marie Watt

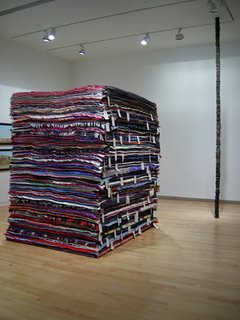

Dwelling, 2006

Wool blankets, satin and wool felt bindings, thread

72 x 66 x 84

Staff, 2006

Cast bronze

3 x 3 x 168

Courtesy of the artist and PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, OR

Marie Watt is a Native American artist, who is also informally known around The Aldrich Museum as the “artist doing the Blanket Project.” Her mother’s side of the family is Seneca, from upstate NY, which was part of the Iroquois Confederacy. She grew up and has lived most of her life in the Pacific Northwest, and she currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

For the past seven to eight years, Marie has worked primarily with blankets. Looking at Native American traditions with blankets, there is first the meticulous craft and material sensibility associated with them, but secondly, and less known, there is a great social connotation with blankets in how they are traditionally given to one another during various times in one’s life. There is this continuing history with blankets that far exceeds the way we look at a blanket as just something to put on in the winter time. Native Americans view a blanket as literally a shelter. From sleeping outside or on the ground wrapped in a blanket, it often carries the role of a shelter. The blanket project is called Dwelling. It will be exhibited in the South Gallery and will take the sculptural form of a stacked pile of nine hundred or more flat wool blankets. Reaching approximately seven feet in height, it will be a giant volume, almost a cubic volume of wool. The majority of blankets are being bought, but also blankets donated by people local to The Aldrich Museum will be incorporated. Along with each blanket, Marie asked donors to add a tag telling the story of their association with this particular blanket.

The social role of the blanket is really important to Marie. This whole project was conceived in a way so as to make a piece of art that also has a life even after leaving the Museum. She intends for it to continue as an instrument for social change and social good. That said, the newly purchased blankets (of the nine hundred, there are approximately six hundred new blankets) will be distributed to homeless shelters and other aid agencies in Fairfield County. So after coming into the Museum, they will go out into the community and serve another important social role.

In addition to Dwelling, there is a smaller blanket collage piece that will hang in the exhibition, which references the life and work of Joseph Beuys. Joseph Beuys is the European artist (died in the 1980s) who was very interested in shamanism. He coined the term “Social Sculpture” through such works that always had a social component or purpose. For example, by planting trees as a work of art, he founded the Green Movement in Germany during the 1970s. Stories of Beuys as a young man recount him as a pilot for Nazi Germany in WW2, who when flying over Russia was shot down. As the story goes, he was found by Russian peasants, freezing, and almost dead. He was wrapped in felt, grease and fat to be kept alive, and this experience and the use of these materials informed his work for the rest of his life. By looking at shamanistic traditions of how artwork and performance could be transformative things, Beuys had his artwork take on a much more important purpose as an agent that could affect society.

One of his most famous performances in NYC was living in a gallery with a coyote. The reasoning behind this was that in Native American mythology the coyote carries symbolism as a trickster and as a cultural hero. He appears in many legends and is responsible for many things, including the Milky Way and the diversity of mankind. So by spending time with the coyote, and by communing with it, Beuys was playing the role of shaman and interceding between humanity and the powerful good and evil spirits. As an homage, Marie made this collage, called Hello Joseph. Since Beuys often carried a cane around, and because Beuys’s sculptures were quite often made of gray wool, Hello Joseph has a coyote figure with a cane, and is entirely made from gray wool blanket fragments.

If Joseph Beuys were still alive today, he would most likely approve of and champion Dwelling for its role as an instrument of social good and change. Each of the blankets has been customized by a group of local project enthusiasts who have sewn colored bindings onto each blanket. So, as opposed to receiving just a gray institutional blanket, these blankets will be something that is specially tailored for each recipient. In addition, this process has brought people together to collectively do good for others.

Edie Winograde

Edie Winograde

A Day in the Life of Lewis and Clark I, 2002

Battle of the Little Bighorn II, 2004

Battle of the Little Bighorn (Finale), 2004

Custer’s Last Stand I, 2004

Custer’s Last Stand II, 2004

Sitting Bull Decides to Fight, 2004

All archival ink-jet prints on watercolor paper, Edition #1/10

18 x 48 each

Edie Winograde is a non-Native artist. She lives most of her year in NYC, but also spends time out in Denver, Colorado. She is a photographer by practice who focuses on historic reenactments for subject matter. She travels around the country and visits places where these re-creations take place.

For No Reservations, we will display her work that documents the two versions of the “Battle of the Little Bighorn” reenactment. One re-creation takes place on reservation land, whereas the other takes place on non-reservation land. She goes to these events with a wide-angle camera and photographs their occurrence.

They are rather fascinating productions because Native and non-Native people participate in both reenactments. During high tourist season, they take place every day. Bleachers are provided for viewers to pay and watch the “battles” take place. The two battle sites are about thirty miles away from one another and they are prominent tourist attractions in the area. They draw both Native and non-Native crowds, and it is also a big thing, evidently, for Japanese tourists.

The romance of the American West and the “cowboys and Indians” American stereotype is still something that is deep set in the American character. Also, in terms of Native American history, this is an important battle because of the fact that General Custer was killed here, and it was viewed as a major military victory for the Sioux and one of the few times that Native people gave the US government “what was coming to it,” in a manner of speaking! These reenactments are rather curious social landscapes. If you look at most of Edie’s photographs you can see an RV or another clue that makes you understand that this is not the 1860s. It is important to note that these photographs are not staged, but rather are documentations of already-occurring events.

Yoram Wolberger

Yoram Wolberger

From the Cowboys and Indians series:

Red Indian #1 (Chief), 2005

91 1/2 x 76 3/4 x 19 1/4

A/P #1

Cowboy #1 (Gunslinger), 2006

84 x 47 x 24

A/P #1

Indian #2 (Bowman), 2006

99 x 68 x 22

A/P #1

Courtesy of the artist, Mark Moore Gallery, Santa Monica, and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco

All 3-D digital scanning, CNC digital sculpting, reinforced fiberglass composites, pigmented resin coating

Yoram Wolberger is a non-Native American artist who lives in San Francisco and was born and raised in Israel. Most of his recent work has dealt with warfare and war through the eyes of children’s toys. Up until this series with cowboys and Indians, he was working with army toys and army men figurines. He is interested in blowing toys up to immense size. By taking an innocent little toy and enlarging it in exactly the same proportions, you begin to look at it in a different way. We will display three of his sculptures based on toy cowboys and Indians, both inside and outside the Museum.

Yoram’s process involves scanning these small toys with a 3-D digital scanning device. After they have been recorded, he then enlarges them (blows them up) to life size. By doing it this way, every flaw is kept. All the flashing on the cowboy, due to the distortions of the small original mold, are retained. These great distortions are bountiful, especially when one views the work from various angles. These vast and bizarre features are much more evident and interesting when we are able to look at the figurine enlarged. The artist is interested in looking at something we are all familiar with, but when suddenly it is made larger it becomes monstrous and the flaws become very evident.

There will be a blue cowboy holding a gun on the Balcony overlooking the lobby. And there will be two red Indians in the interior courtyard, so it will be like a range where they are confronting one another, as if some child has arranged them for battle.

A little background on Yoram: as a child in Israel he grew up with these toy cowboys and Indians. Military service was a national requirement and he eventually served in the Israeli army and engaged in battles with Palestinian people as a young man. After a while, he decided that he had enough of that and he wanted to leave Israel. He moved to the United States, married, and now lives in San Francisco. One thing that he is very interested in for his subject matter is the correlation between colonialism and the Native American predicament. One of the last great acts of the British Empire, in terms of getting rid of their colonial entities, was dealing with Palestine after WW2. This division of Palestine, creating Israel, and displacing the Palestinian people, is very similar to Native American reservations, and is also a problem that still haunts us today.

Being an Israeli in the US and looking at US history and Native people on reservation lands, he is very aware of how humans control land. Land control can be autonomous, as in free nation states, or completely controlled. In looking at Yoram’s work, one can make some equation between Native Americans and the Middle East, especially through his choice of materials. All of these toys are made from plastic, which is made from petrol chemicals. Yoram is very aware of this. These big sculptures are similarly made out of fiberglass, which is epoxy, which is made from oil.

The idea that the little toys look powerful and respectful only goes so far. One might say that they are proud Indian braves or Indian chiefs, yet Major League Baseball teams have been forced to change their mascots and logos due to stereotyping. Many Americans have grown up to accept these as cute and innocent toys, but when you blow them up and they become these grossly distorted, weird objects, one can more readily see how these toys really deal with the grossest type of stereotyping, simply because it is so ingrained, innocuous, and introduced at such an early age. Also, we still give these to kids! They are sold at Ridgefield Hardware right by the cash register. We like to think that we don’t teach our children stereotyping, but the fact is you can see it in so many toys.

This text has covered at least one example of a work by each artist in the exhibition. There is a lot to digest, seeing as this is a very complicated project.

The number of things you can talk about in this exhibition is overwhelming. The thing about this exhibition is that it raises more questions than it answers. I think it allows people to look at the range of work that’s going on and then pick the things that are most memorable. We are pleased and excited because we anticipate that people are going to remember work from this exhibition. We envision it creating many lasting impressions.

Docent Notes

Richard Klein

Bill Schott

White Providence and American Indian Circumstance

Notes on

No Reservations: Native American History and Culture in Contemporary Art

No Reservations is a group exhibition of ten contemporary artists whose work focuses in one way or another on the history of Native American people and culture, on view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum from August 23, 2006, to Feb 25, 2007.

Of the exhibiting artists, those who are non-Native seem to be generally more interested in the history of Native Americans because it sheds light on the supposed “American Character.” The Native contingent in the exhibition seems to be more interested in reclaiming Native American culture and traditions. In either case, the central story of the United States and the occupation of North America, the dislocation of Native people, and their genocide, is one that we all know. However, one might argue that this history is not as readily accessible or thought of as much as other histories. By bringing together this collection of work, No Reservations examines the Native American culture through a lens of contemporary art-making.

Lately, there is the expectation in Germany that younger generations have come to terms with the Holocaust and their country’s Nazi history. In general, the younger generation is more able to deal with it. This is evident through the willingness to engage in conversations that would not have taken place during the 1950s and 1960s. This sort of openness has never really occurred regarding the history of the Native Americans and the United States. When you look at the extreme things that were done to the Natives, in particular between the 1840s and the 1890s, you see that similar atrocities were committed, only that these seem to have been forgotten or, even worse, swept under the carpet.

Upon investigation, one quickly learns about an unbelievable string of lies that were told to Native people; of treaties signed and murderous acts committed on behalf of the American Government—it really is a horrible story. This exhibition does not dwell on the past. However, it does acknowledge this history and raises more questions than answers about how we currently view Native American history and culture.

The non-Native artists who are dealing with these issues are looking at this history and are trying to get to some central issue about “American character.” In many ways, it is revealing of human nature in general. It shows the dark side of human nature and what is evil in human beings. By analyzing how this came about, the artists realize how history can inform us, and are making work so that viewers can become aware of it.

Native American culture reminds us that we are all habitants of this land. Regardless of where we came from, we all live here now, and being aware of this tenancy puts us closer in touch with the American landscape. It grounds us. It encourages us to be good citizens and become politically aware of related topics. When you research the American Indian Movement, you realize that what happened was not that long ago in relation to the entirety of human history and recorded time.

Since the subject matter of Native American history and culture is very broad, Richard Klein, the curator, wanted to limit the number of artists (10) so each could show multiple works. This was done deliberately, so that there is a more complete showing of each. Overall, it is an interesting mix because there are many ways to go with this theme. Also, it marks the first time that The Aldrich has shown an artist from Alaska.

MATTHEW BUCKINGHAM

Matthew Buckingham

The Six Grandfathers, Paha Sapa, in the Year 502,002 C.E., 2002

60 x 43 black and white digital c-print, dry-transfer wall text

Installation dimensions variable

Matthew Buckingham is a non-Native American artist, who has moved around frequently. He has lived in New York, London, and other places. He currently lives in Minneapolis.

He has two really amazing projects about Native American history. One of them is entitled The Six Grandfathers, Paha Sapa. It is a large digital photograph of what is now Mount Rushmore, in 1050 BCE. Mount Rushmore is part of the Black Hills. ‘Paha Sapa’ is Lakota, the local Native language, for Black Hills, which were, and still are, sacred lands to the local Natives.

Matthew’s photograph documents what the Black Hills will look like in 500,000 years from now. It shows how the United States monument will get to the point where you cannot recognize the faces of the presidents anymore. The work also includes the history of this region from prehistoric times to today.

In researching the Native American language one finds that the English language has changed the names for many things. For instance, the name Dakota is an American version for Lakota. Both refer to the same thing, except that there is some controversy over what constitutes tribal names, since many names were given by early European American settlers. Currently, there is a movement to go back to the old/ original names.

The accompanying timeline in this work outlines the affront that was given to Native people with regard to the Black Hills and the construction of Mount Rushmore. It dates significant geological occurrences, as well as the corrupt politics of the US government when it was being made. Gutzon Borglum, the creator of Mount Rushmore, had previously worked on Stone Mountain in Georgia. There are only four presidents depicted because he only had the budget to carve four of them.

When thinking about the significance of this work, it is important to think that here is a European-American artist focusing on an iconic American image (Mount Rushmore). He is projecting forward in geologic time, instead of looking back, making the point that nothing lasts forever. The permanence of all things fades. Even the most resilient empires crumble. There is a common misconception about the idea of owning land and drawing boundaries (house fencing, state and national borders). A concept of Native American teaching is that it looks at land ownership in a much different way. Territory and homeland still exist, it is just a much more fluid thing. We only borrow the land we live on while we are alive.

LEWIS deSOTO

Lewis deSoto

CONQUEST, 2004

Full-size customized motor vehicle

4 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. 6 in. x 18 ft. 6 in.

Lewis deSoto is a Native American artist who grew up in Napa, California. His paternal great-grandfather’s side of the family is linked to both the Cahuilla tribe and to ancestors of Hernando DeSoto, the sixteenth century Spanish conquistador. His great-grandfather was from the same small town in Spain as Hernando DeSoto. With the same last name (though different capitalization), the artist believes they are blood-related, though they still lack official documentation. Regardless, Lewis deSoto’s great-grandfather, after moving to North America, married a member of the Cahuilla tribe. Lewis therefore has relations to both the “conquered” and the “conquerors.”

For this exhibition, deSoto will present two cars in the Museum lobby and Project Space.

In the lobby is an automotive self-portrait that conceptually references the history of Hernando DeSoto, the Spanish conquistador who pillaged southeast and midwest America in search of New World riches during the sixteenth century. From the 1920s to the 1960s, Chrysler owned a marque named after the Spanish conquistador, entitled “DeSoto.” Well, Lewis deSoto grew up in California and became fascinated with car culture. While growing up, and to this day, Lewis was frequently asked if there is a connection between his family and this car company. The DeSoto company went out of business in 1961, and the line of cars was discontinued. Lewis has since found an older Chrysler model and restored and fabricated it to become what he now refers to as a 1965 DeSoto CONQUEST. People who know a bit about cars will ask how there is a 1965 model. To this Lewis replies, “they continued production in Canada for a couple more years.” Of course, in fact, they did not!

Apart from using an older model as the platform, Lewis deSoto also redesigned instruments, wheel covers, roof designs, monikers, upholstery, color schemes and mechanical characteristics to suit the concept of the CONQUEST. In addition, the owners manual and window sticker include the Requiremento, the legal document read to Native peoples before their submission to Spain (poster of this will hang in the exhibition space). Overall, this design is meant to mesh with the idea of synthetic histories of DeSoto’s supposed conquest of the Americas.

LEWIS deSOTO

CAHUILLA, 2006

Full-size customized motor vehicle with ambient soundtrack

6 ft. 6 in. x 7 ft. 11 in. x 18 ft.

Tapestry weaving courtesy Magnolia Editions, Oakland, CA

The second piece by Lewis deSoto is the CAHUILLA pickup truck. It is a 1981 GMC pickup converted into a new model called the CAHUILLA. The vehicle is named after his great-grandmother’s tribe; the Cahuilla tribe has a casino and has made quite a bit of money recently. This truck is looked at by the artist as a symbol of the Cahuilla culture and has incorporated traditional views from their history. It also incorporates the reality that many Indian tribes are involved with recent casino development. When you look down from the balcony of the Project Space upon this piece, you will see a woven tapestry stretched over the bed of the truck. Traditional Cahuilla designs are used along with black diagrammatic drawings that represent a craps table from a casino. A soundtrack of Native chants with ambient noise from slot machines will play on the internal sound system in the truck. In addition, the truck has all sorts of subtle things: from the traditional necklace made by his grandmother hanging from the rear view mirror, akin to a talisman (like a spirit catcher), to seat covers that are custom-woven with a pattern from the complicated lacy border design of the dollar bill. There is a teepee symbol as an automotive logo on the side of the vehicle, as well as a bumper sticker that says “Buy America Back!” This isn’t far from the truth. Aside from casino implications, the Pequots, for example, are literally buying real estate back in eastern CT and providing a great deal of business for major commercial real estate agencies. In many ways, the money from casinos is indeed buying Native American land back. The trick then, for the Native Americans, is in getting the US government to concede and recognize this bought-back land as additional legalized reservation territory. There are many legal incentives for tribes to obtain federal recognition, primarily, the absence of taxation for reservations in the US tax structure.

Lewis’s CAHUILLA project underscores these economic issues and what Native peoples are doing to become financially successful today. He is imagining this truck as being owned by a wealthy casino-working Cahuilla, who lives on the reservation. This exhibition is occurring at a time when immigration is a huge issue for the United States. The comparison of European immigration to North America and the displacement of Native peoples in relation to this contemporary movement of people from Latin America to above the Rio Grande, is most intriguing. The economic displacement that comes from this movement of people, and then the associated politics surrounding financial and territorial ramifications, can become rather cutthroat. However, it is nothing new to civilization. This sort of thing occurs frequently throughout history and all over the world. It is a phenomenon of spatial relations within human existence.

It is well known how American car manufacturers love using Native-American names (e.g. Pontiac, Tacoma, Cherokee; there is a new pick up “Denali” that is named after the tallest mountain in the US, Mount McKinley, Denali is the native name for this location). The car as an object is a symbol of the American landscape. Think about Manifest Destiny and the spread of European civilization in North America. Wagon trails, railroads, and then the automobile. It has led to the subsequent alteration of the environment, with the building of the Interstate highway system, which, probably more than anything else, is responsible for the destruction of so much of natural North America. It has allowed urban sprawl, the kind of suburban development that is endemic in the US because of the car. If you look at the landscape as sacred, the car is the tool that has been the landscape’s undoing more than anything else.

PETER EDLUND

PETER EDLUND

Majestic America: Rape of the Modoc in Yosemite (After Albert Bierstadt), 1999

Oil on Canvas

36 x 50

Collection of John Burger, M.D.

Peter Edlund is a non-Native artist who lives in NYC. His work from the past fifteen years primarily focuses on radical repainting of nineteenth-century American Hudson River School landscape paintings. Artworks from artists such as Albert Bierstadt or James Audubon are mimicked. Yet, all of Peter’s work does not deal with native history. Peter uses the nineteenth century as a lens to talk about the present day. The fact that the nineteenth century was such a formative period for the United States is a corollary. He uses Audubon’s images and Hudson River painters to talk about ecological concerns. He has created work focusing on Native Americans from part of a series called Majestic America. One of these pieces, entitled The Rape of the Moduk at Yosemite Valley, is after Bierstadt. In 1864, the year the original painting was created, the then California authority instigated genocide against the Moduk Indians, who live in the Sierra Mountains. Peter has taken the history of this time and incorporated subtle changes into the landscape painting. The first, which is the most obvious, is that the color is very apocalyptic, menacing and intense. This painting is done to the exact same size as the original and oddly enough it is owned by Sprint and hangs in their corporate headquarters when not on exhibition. Also, subtle changes are visible in the shadows of the painting. When looked at closely, one can see shadowy figures where the Moduk are being raped. Peter has included this change to the painting so as to incorporate the history of 1864. In the painting by Bierstadt, one can see the figures doing something, though it is too hard tell what is going on.

There will be three paintings in total. For this exhibition, he is producing a new version of Frederick Church’s painting of West Rock in New Haven. So it is specifically about CT. Within his work, he studies native language place names. For instance he will look into names like, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Housatonic, Katonah, in order to find the original meaning from the local Native language and will then paint a picture, from his imagination, of the literal translation for the place name. Creating an image from the language is like going backwards with the typical painting process. These paintings will exist in the Project Space with deSoto’s CAHUILLA pick-up truck.

NICHOLAS GALANIN

NICHOLAS GALANIN

Tlingit Raven Vol. 14, 2006

Paper: 1700 pages containing text from Under Mount Saint Elias

6 x 9 x 4

Courtesy of the artist

Nicholas Galanin, a Native American, is the first artist from Alaska to exhibit at The Aldrich Museum. He is from Sitka, Alaska and is part of the Tlingit (pronounced Clink-get) tribe. Of all the Native artists in the show, Galanin summarizes the position that so many Native artists have, with one foot in two different worlds. On one hand, he makes traditional Tlingit artworks, such as wood carvings, totem poles, and other massive wooden objects that are unbelievably accomplished works that are dedicated to his people. At the same time, he also produces contemporary artworks to engage the outside world. His Web site reflects this in how it is divided into two halves (Traditional and Contemporary).

For this exhibition, three works by Nicholas—one video, and two small sculptures—will be shown. One sculpture, entitled Tlingit Raven Volume 14, is taken from a traditional carving of a raven from within Tlingit culture. The contemporary twist is that it is made from pages within a book—approximately 1700 hundred pages from the book Mount Saint Elias, published in 1972 by anthropologist Frederica de Laguna. Laguna was a contemporary of Margaret Mead, and made the definitive study of the Tlingit culture by an anthropologist. All of Galanin’s work is based in this idea that Native people are defined by, or know their history through Western anthropology. So much was destroyed culturally, yet anthropologists are the ones who piece it back together. It is important to note that they are not Native but European. Therefore, Galanin is creating a traditional Tlingit image made out of writings in which a Western anthropologist describes his culture. It is about how a culture gets recreated, or how the culture looks at itself.

JEFFREY GIBSON

JEFFREY GIBSON

Mythmaker, 2006

Wood, urethane foam, oil paint, glass beads, pigmented silicone

114 x 54 x 54

Jeffrey Gibson is a Native American artist. His mother’s side of the family is part of the Choctaw (pronounced chalk-ta) tribe from Mississippi. His father is an engineer and he grew up traveling around the world, living in Germany and other places. He has been exposed to a great deal of international influence, but spends a lot of time in Mississippi on his reservation. He is an example of an artist in the exhibition who incorporates Native/cultural influences in ways that are most unexpected. In the exhibition, he is the Native artist whose work is most devoid of politics. He is really interested in the idea of looking at Native art prior to colonization, and how it was engaged in nature in a very celebratory way.

JEFFREY GIBSON

Residual Urge, 2006

Urethane foam, wood, pigmented silicone

148 x 115 x 27

Silicone courtesy of General Electric Company, Fairfield, CT

He will have both a large sculpture and some paintings on exhibit. His sculpture will be hanging on the outside front of the Museum by the bay window. A foam-filled form covered by millions of silicone rubber beads. It will be heavily textured and mostly black, but with a few flashes of color (red and blue). This way of working is in many ways a continuation of Iroquois pieces called “Beaded Whimsies.” In the nineteenth century, the Iroquois were very poor and to make money made beaded objects for tourist sale. They would make things using traditional beaded techniques, like picture frames, lampshades, and bags. The beading got so intense that some of these objects would become functionally unusable due to the amount of adornment. So here we have a Native beading tradition that was subverted by commerce and turned into a bizarre art form that was very popular for a thirty-year period.

Fully aware of this history, Jeff is now making the largest beaded whimsy ever made. Instead of glass beads he beads with silicon rubber. The complicated beaded surface that covers this foam object turns it into a rather odd and anomalous thing that will hang from the top of the Museum. It can be considered a subversion of the colonial architecture of the Museum, as this piece will also hang in the historic district of Ridgefield. In fact, almost all the houses on downtown Main Street are based in a European architectural style that was predetermined by early accepted colonial aesthetics. So this odd object on the face of the Museum is potentially turning the tables around on this European American aesthetic, by exposing this great growth of Native American financially-necessary adornment. One could critically acclaim this work with heavier politics of building upon the Iroquois tourist trade, but the artist thinks of it much more as a celebratory thing.

RIGO 23

RIGO 23

Taté Wikikuwa Museum, 1999-2006

Mixed media installation

Dimensions variable

Leonard Peltier paintings on loan from L.P.D.C.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco

The sign out by the street that says, “The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum” has a convenient blank space right under the Aldrich text on the glass. When you come to The Aldrich Museum during the months of No Reservations (starting on August 23), you will be surprised to see that the sign will also feature text that reads Taté Wikikuwa Museum. When you come up the walkway to the Museum, you will also see Taté Wikikuwa Museum on the front of the building, and on the rear of the Museum, in raised letters it will say Taté Wikikuwa Museum. Taté Wikikuwa is the name of Native American activist Leonard Peltier in his Lakota language, meaning “wind chases sun.”

The Aldrich will host this homeless museum that travels around the world and is dedicated to Leonard Peltier, who has been in prison for thirty years. This is a work by an artist named Rigo 23. Yes that is his name, and every couple of years, he changes the number at the end of his name (e.g. Rigo 42, Rigo 99 etc.). Rigo is from the Madeira Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, owned by and just off the coast of Portugal. Curiously, it was a way station for Columbus before he traveled to the New World. Columbus even briefly lived there. Rigo 23 lives in the San Francisco Bay area today and is a social activist. His first work was a mural painting in the spirit of Mexican Muralists. In San Francisco, he was part of the street art phenomenon. However, Rigo’s work was more mural-oriented, with the idea of doing things for communities and giving back to society through art that carries a social purpose. From living in CA, and befriending some Native people, he became aware of Leonard Peltier. Since he is very socially aware and connected, he readily began working with the Native American community.

Leonard Peltier is an American Indian activist who was imprisoned in 1977 for the alleged shooting of an FBI agent on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota. His story is actually the subject of a movie that Robert Redford bankrolled and starred in, made through Sundance Film Festival, entitled Incident at Oglala. It is not a dramatization, but rather more documentary in format, about Leonard Peltier. Rigo has taken it upon himself to work with the Leonard Peltier Defense Fund to try and get him released from prison. Two Native people who were also charged with shooting the agent were released and were never put in prison. Peltier, on the other hand, was charged with aiding and abetting, and, supposedly because he is so vocal, and because of his personality, he was made a scapegoat. In 1999, Bill Clinton was about to release Peltier, but the FBI found out about it, and since they are vehemently against Peltier, they stopped this. In 2008 he is coming up for parole again. He was sentenced to two consecutive 25-year terms, plus a 7-year term for a related crime. At this parole meeting there is the possibility that the board may choose to have him serve his terms concurrently instead of consecutively, so that he could be released in 2008.

Rigo 23 has taken this Taté Wikikuwa Museum around the world (San Francisco, Brazil, Spain, England, etc) to increase consciousness of Peltier, in the hope that the people who see the exhibition will write to the parole board to urge his release. Apparently, parole boards really pay attention to letters. From Amnesty International, to Mother Teresa, to Desmond Tutu, the list of people who support him is rather extensive. Outside the United States he is looked upon as a major political prisoner of the US.

So, in the Balcony Gallery, Rigo 23 will display the museum—a recreation of Peltier’s prison cell. On the back stairwell, dates will go down each step for every year Peltier has spent in prison. In addition, there will be a selection of the paintings Peltier paints in prison. We are actually borrowing these from his legal Defense Fund. The windows will have bars on them so as to recreate the environment of being contained in prison. Information about Peltier and how to contact the parole board will also be made available.

Before I said that the non-Native artists are primarily dealing with history, well this is living history, and this is also with regard to something that happened not too far in the past (from the 1970s). Too many Americans have forgotten about the American Indian Movement (AIM) and how important it was and still is. One thing about Rigo 23’s involvement with Peltier’s Defense Fund, is that he is greatly increasing consciousness of a period of American history that was vital for Native Americans. Nowadays, when you mention Peltier’s name, most people have no clue who he is. So this work acts to remedy that and hopefully aid in his release.

DUANE SLICK

DUANE SLICK

Looking for Orozco (detail), 1993

Mixed media artist’s book on Mylar

15 double-sided pages excerpted from the 17 page book.

Each 22 x 15 1/4

Courtesy of the artist and Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA

Duane Slick is a Native American artist who is most connected with the Sauk and Fox tribe in Iowa. These people were displaced from the Ohio River Valley. He has recently been spending time out there because his father is very ill. When not in Iowa, he is a professor of painting at RISD.

Duane does two very different bodies of work. One informs the other. The first is a series of artist books, which he has shown in various formats. We will be showing the majority of the pages from an artist book that is a narrative that weaves the influence of Mexican mural painters, from when he was a young man, to his desire to make art that has a social purpose. It includes many experiences that the artist has had with his family, through his relatives, and personally, that pertain to Native American culture.

DUANE SLICK

Looking for Orozco (detail), 1993

Mixed media artist’s book on Mylar

15 double-sided pages excerpted from the 17 page book.

Each 22 x 15 1/4

Courtesy of the artist and Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA

Each page will be hung off the wall perpendicularly and the pages are two-sided. Walk down the wall and look at both sides to read the narrative. The book deals with all sorts of interesting things, including how the artist rejected Jackson Pollock as an influence. A theme that runs through most of the Native work in the exhibition, is being influenced by modernism and working within the modernist tradition, but at the same time wanting to reject it, and wanting to go back a step somehow.

Also on view will be one large painting by Mr. Slick. Duane’s paintings combine Native American mythology and contemporary imagery with a somewhat tragic melancholy feeling. For example, the painting we will show combines an image of an eagle with a wheelchair. We tend to think of the eagle as an all-powerful symbol of Native American and United States cultures. What does it mean when an artist combines it with a wheelchair? It talks about this traditional symbol as being crippled somehow. Also, these images are painted in a very ghostly manner. They could be described as ‘white on white’ paintings and it seems as though he deals with images from a spiritual realm, or images that are not visually apprehended as much as apprehended through one’s mind’s eye, or as a spiritual revelation.

Marie Watt

Marie Watt

Dwelling, 2006

Wool blankets, satin and wool felt bindings, thread

72 x 66 x 84

Staff, 2006

Cast bronze

3 x 3 x 168

Courtesy of the artist and PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, OR

Marie Watt is a Native American artist, who is also informally known around The Aldrich Museum as the “artist doing the Blanket Project.” Her mother’s side of the family is Seneca, from upstate NY, which was part of the Iroquois Confederacy. She grew up and has lived most of her life in the Pacific Northwest, and she currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

For the past seven to eight years, Marie has worked primarily with blankets. Looking at Native American traditions with blankets, there is first the meticulous craft and material sensibility associated with them, but secondly, and less known, there is a great social connotation with blankets in how they are traditionally given to one another during various times in one’s life. There is this continuing history with blankets that far exceeds the way we look at a blanket as just something to put on in the winter time. Native Americans view a blanket as literally a shelter. From sleeping outside or on the ground wrapped in a blanket, it often carries the role of a shelter. The blanket project is called Dwelling. It will be exhibited in the South Gallery and will take the sculptural form of a stacked pile of nine hundred or more flat wool blankets. Reaching approximately seven feet in height, it will be a giant volume, almost a cubic volume of wool. The majority of blankets are being bought, but also blankets donated by people local to The Aldrich Museum will be incorporated. Along with each blanket, Marie asked donors to add a tag telling the story of their association with this particular blanket.

The social role of the blanket is really important to Marie. This whole project was conceived in a way so as to make a piece of art that also has a life even after leaving the Museum. She intends for it to continue as an instrument for social change and social good. That said, the newly purchased blankets (of the nine hundred, there are approximately six hundred new blankets) will be distributed to homeless shelters and other aid agencies in Fairfield County. So after coming into the Museum, they will go out into the community and serve another important social role.

In addition to Dwelling, there is a smaller blanket collage piece that will hang in the exhibition, which references the life and work of Joseph Beuys. Joseph Beuys is the European artist (died in the 1980s) who was very interested in shamanism. He coined the term “Social Sculpture” through such works that always had a social component or purpose. For example, by planting trees as a work of art, he founded the Green Movement in Germany during the 1970s. Stories of Beuys as a young man recount him as a pilot for Nazi Germany in WW2, who when flying over Russia was shot down. As the story goes, he was found by Russian peasants, freezing, and almost dead. He was wrapped in felt, grease and fat to be kept alive, and this experience and the use of these materials informed his work for the rest of his life. By looking at shamanistic traditions of how artwork and performance could be transformative things, Beuys had his artwork take on a much more important purpose as an agent that could affect society.

One of his most famous performances in NYC was living in a gallery with a coyote. The reasoning behind this was that in Native American mythology the coyote carries symbolism as a trickster and as a cultural hero. He appears in many legends and is responsible for many things, including the Milky Way and the diversity of mankind. So by spending time with the coyote, and by communing with it, Beuys was playing the role of shaman and interceding between humanity and the powerful good and evil spirits. As an homage, Marie made this collage, called Hello Joseph. Since Beuys often carried a cane around, and because Beuys’s sculptures were quite often made of gray wool, Hello Joseph has a coyote figure with a cane, and is entirely made from gray wool blanket fragments.

If Joseph Beuys were still alive today, he would most likely approve of and champion Dwelling for its role as an instrument of social good and change. Each of the blankets has been customized by a group of local project enthusiasts who have sewn colored bindings onto each blanket. So, as opposed to receiving just a gray institutional blanket, these blankets will be something that is specially tailored for each recipient. In addition, this process has brought people together to collectively do good for others.

Edie Winograde

Edie Winograde

A Day in the Life of Lewis and Clark I, 2002

Battle of the Little Bighorn II, 2004

Battle of the Little Bighorn (Finale), 2004

Custer’s Last Stand I, 2004

Custer’s Last Stand II, 2004

Sitting Bull Decides to Fight, 2004

All archival ink-jet prints on watercolor paper, Edition #1/10

18 x 48 each

Edie Winograde is a non-Native artist. She lives most of her year in NYC, but also spends time out in Denver, Colorado. She is a photographer by practice who focuses on historic reenactments for subject matter. She travels around the country and visits places where these re-creations take place.

For No Reservations, we will display her work that documents the two versions of the “Battle of the Little Bighorn” reenactment. One re-creation takes place on reservation land, whereas the other takes place on non-reservation land. She goes to these events with a wide-angle camera and photographs their occurrence.

They are rather fascinating productions because Native and non-Native people participate in both reenactments. During high tourist season, they take place every day. Bleachers are provided for viewers to pay and watch the “battles” take place. The two battle sites are about thirty miles away from one another and they are prominent tourist attractions in the area. They draw both Native and non-Native crowds, and it is also a big thing, evidently, for Japanese tourists.

The romance of the American West and the “cowboys and Indians” American stereotype is still something that is deep set in the American character. Also, in terms of Native American history, this is an important battle because of the fact that General Custer was killed here, and it was viewed as a major military victory for the Sioux and one of the few times that Native people gave the US government “what was coming to it,” in a manner of speaking! These reenactments are rather curious social landscapes. If you look at most of Edie’s photographs you can see an RV or another clue that makes you understand that this is not the 1860s. It is important to note that these photographs are not staged, but rather are documentations of already-occurring events.

Yoram Wolberger

Yoram Wolberger

From the Cowboys and Indians series:

Red Indian #1 (Chief), 2005

91 1/2 x 76 3/4 x 19 1/4

A/P #1

Cowboy #1 (Gunslinger), 2006

84 x 47 x 24

A/P #1

Indian #2 (Bowman), 2006

99 x 68 x 22

A/P #1

Courtesy of the artist, Mark Moore Gallery, Santa Monica, and Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco

All 3-D digital scanning, CNC digital sculpting, reinforced fiberglass composites, pigmented resin coating

Yoram Wolberger is a non-Native American artist who lives in San Francisco and was born and raised in Israel. Most of his recent work has dealt with warfare and war through the eyes of children’s toys. Up until this series with cowboys and Indians, he was working with army toys and army men figurines. He is interested in blowing toys up to immense size. By taking an innocent little toy and enlarging it in exactly the same proportions, you begin to look at it in a different way. We will display three of his sculptures based on toy cowboys and Indians, both inside and outside the Museum.

Yoram’s process involves scanning these small toys with a 3-D digital scanning device. After they have been recorded, he then enlarges them (blows them up) to life size. By doing it this way, every flaw is kept. All the flashing on the cowboy, due to the distortions of the small original mold, are retained. These great distortions are bountiful, especially when one views the work from various angles. These vast and bizarre features are much more evident and interesting when we are able to look at the figurine enlarged. The artist is interested in looking at something we are all familiar with, but when suddenly it is made larger it becomes monstrous and the flaws become very evident.

There will be a blue cowboy holding a gun on the Balcony overlooking the lobby. And there will be two red Indians in the interior courtyard, so it will be like a range where they are confronting one another, as if some child has arranged them for battle.

A little background on Yoram: as a child in Israel he grew up with these toy cowboys and Indians. Military service was a national requirement and he eventually served in the Israeli army and engaged in battles with Palestinian people as a young man. After a while, he decided that he had enough of that and he wanted to leave Israel. He moved to the United States, married, and now lives in San Francisco. One thing that he is very interested in for his subject matter is the correlation between colonialism and the Native American predicament. One of the last great acts of the British Empire, in terms of getting rid of their colonial entities, was dealing with Palestine after WW2. This division of Palestine, creating Israel, and displacing the Palestinian people, is very similar to Native American reservations, and is also a problem that still haunts us today.

Being an Israeli in the US and looking at US history and Native people on reservation lands, he is very aware of how humans control land. Land control can be autonomous, as in free nation states, or completely controlled. In looking at Yoram’s work, one can make some equation between Native Americans and the Middle East, especially through his choice of materials. All of these toys are made from plastic, which is made from petrol chemicals. Yoram is very aware of this. These big sculptures are similarly made out of fiberglass, which is epoxy, which is made from oil.

The idea that the little toys look powerful and respectful only goes so far. One might say that they are proud Indian braves or Indian chiefs, yet Major League Baseball teams have been forced to change their mascots and logos due to stereotyping. Many Americans have grown up to accept these as cute and innocent toys, but when you blow them up and they become these grossly distorted, weird objects, one can more readily see how these toys really deal with the grossest type of stereotyping, simply because it is so ingrained, innocuous, and introduced at such an early age. Also, we still give these to kids! They are sold at Ridgefield Hardware right by the cash register. We like to think that we don’t teach our children stereotyping, but the fact is you can see it in so many toys.

This text has covered at least one example of a work by each artist in the exhibition. There is a lot to digest, seeing as this is a very complicated project.

The number of things you can talk about in this exhibition is overwhelming. The thing about this exhibition is that it raises more questions than it answers. I think it allows people to look at the range of work that’s going on and then pick the things that are most memorable. We are pleased and excited because we anticipate that people are going to remember work from this exhibition. We envision it creating many lasting impressions.